Multimedia Art: a Sacred Unity

A Text by Aleksi Barrière

Multimedia Art: a Sacred Unity

A Text by Aleksi Barrière

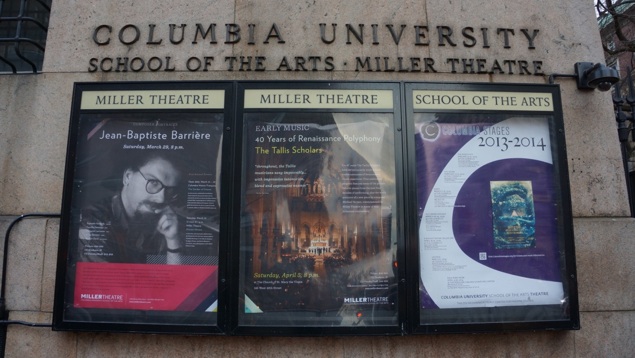

The following text was written at the occasion of Jean-Baptiste Barrière’s «Portrait Concert » at Miller Theater (New York), March 29th, 2014, and of other related events organized around it:

http://www.millertheatre.com/events/jean-baptiste-barriere

http://www.millertheatre.com/events/special-performance-distant-mirrors

see the page on the Portrait Concert on this site

Multimedia Art: A Sacred Unity

“I believe also that perhaps the monstrous atomistic pathology at the individual level, at the family level, at the national level and the international level - the pathology of wrong thinking in which we all live - can only in the end be corrected by an enormous discovery of those relations in nature which make up the beauty of nature.”

Gregory Bateson, A Sacred Unity: Further Steps to an Ecology of Mind

Jean-Baptiste Barrière belongs to a blessed generation of French artists who were born after World War II, and who turned twenty in the midst of an academic boom that allowed them to gorge themselves on the revolutionary lectures of Foucault, Deleuze, Derrida, Lyotard… and who simultaneously benefitted from the golden age of cultural policies and subsidies, following François Mitterrand’s election as a President in 1981. Barrière also witnessed the creation and development of increasingly sophisticated technologies, and very early on anticipated their artistic potential, leading to his interest in computer programming and his commitment to the activities of IRCAM, a recently founded institution that would embody the adventurous spirit of the time, when the birth of electronic sound-synthesis seemed to open up a new era in world music.

It is important to remember this history in order for us to recall IRCAM not as the cold laboratory of a mad scientist, but as a hive where everything seemed possible, especially in the 80s for a young composer. The gradual popularization of such sophisticated technology, increasingly user-friendly, seemed to redeem the technical civilization that had been doomed by the horrors of industrialization and technological mass-murders. In the age of post-structuralism and cybernetics, the recent discoveries in genetics were not reminiscent of Nazi experiments, but seemed to unlock new levels of understanding of reality, and to comprehend –meaning, to invent– in a new, global fashion our place in the universe. Along with computers rose ecology. The radical philosophy that impregnated the minds of the young artists was full of concepts such as rhizomes, deterritorialization, power-knowledge, deconstruction of metanarratives, and influential moments of the history of science, such as epigenetics, catastrophe theory and significant breakthroughs in particle physics or astrophysics –each of them challenging usual patterns of thinking as well as many artists’ imagination, therefore bearing a potential artistic program of its own. Art was bound to be a laboratory not only of form, but also of society.

Jean-Baptiste Barrière never gave up on the ideals of his learning years. His attempt at reuniting disparate parameters between forms of art in the most coherent way has actually been so meticulous, that it has resulted in a rare, scarce and refined body of work that can hardly be compared to what we are used to call a composer’s “repertoire” or a visual artist’s “portfolio”. Rather than a catalogue of scores, it presents itself as a series of collaborations –––between arts and people. While many artists of his generation that had been involved in the supposed dawn of multimedia art gradually developed the same kind of careers their scorned teachers had, combining power in the institution and a routine of state commissions, and often confining themselves into their own respective arts, Barrière kept on developing a research that had little to do with trying to make one’s way into the repertory of world-famous string quartets or being part of international art fairs. Inspired by those “patterns that connect” Gregory Bateson found in nature, and that secured the unity of reality, he sought to build cultural unity between arts that virtually ignored each other, with the help of technology whose main attribute is to ‘crystallize’ these patterns, as Gilbert Simondon puts it.

Each methodological step is essential to his global process: studying mathematical logic to be able to master computing processes and use them as creative tools; in the framework of IRCAM, breaking sound down to its smallest components in order to synthesize it, or analyzing scientifically the nature of perception; exploring the latest hardware and software improvements that might generate interactivity in artistic creation; applying sound synthesis processes to image, and thematically looking for solutions in masterpieces from the past history of visual arts, in the attempt of rethinking how pictures can be created in new media. Steps of this organic process can be found in the landmark pieces that will be heard tonight: the clarity with which they can be recognized –in works that span over thirty years– highlights all the more remarkably how steady this process has been. Recurring themes/techniques (two concepts we cannot separate in this context) that will guide us throughout this overview are for instance the conflict between natural and artificial (whether synthesized or processed), the thin border between description and representation within abstract media, the many-leveled use of recurring patterns and structures, and one sound/image hiding or revealing the other through mixing. The moveable set of screens in which we are presenting this program, in its combinatorial variations and gradual unveilings, implicitly highlights these processes.

These are pieces that do not set statements to music, but rather search for the narrative intrinsic to various media and forms. Tension being the first and foremost element of horizontal composition (whether in music or in cinematic art, that were Barrière’s two main interests in the beginning of his career), its construction makes concrete use of Maurice Maeterlinck’s and Simone Weil’s ideas of forces of violence roaming through the world, and being locally unleashed with destructive effects that can never be made sense of. The mystery of violence is indeed a major theme here –but rather than emphasize its mainstream, graphic translation, this set of performances creates force fields that bring us into subtle sensorial experiences that ultimately not only challenge our perceptive patterns, but also apprehend phenomenological reality in a way perhaps more truthful.

Multimedia should not mean, as it often does in practice, to mediate a message in multiple and separate ways –instead, it should be about exploring pathways that connect media is a process that has the potential to underline the fundamental interconnectedness of reality. A reality we belong to, as we often tend to forget. Multimedia art is a wrestle against the ‘atomistic pathology’ coined by Gregory Bateson in his last lecture, in words that have always been inspirational to Jean-Baptiste Barrière. It is a place that allows the study of the structures and relations in nature (our bodies, the universe), and working within them. A fascinating place to be; not to try and transform these natural structures, which are not ours to tamper with, but to serve as a workshop for those structures we construct culturally and politically in our lives and societies, and which are entirely in our own hands.

Aleksi Barrière, March 2014.

Poster of the event on the front of Miller Theatre

Margaret Lancaster rehearsing Crossing the Blind Forest

Aliisa Barrière rehearsing Violance

AAleksi Barrière rehearsing the staging for Ekstasis with Raphaële Kennedy